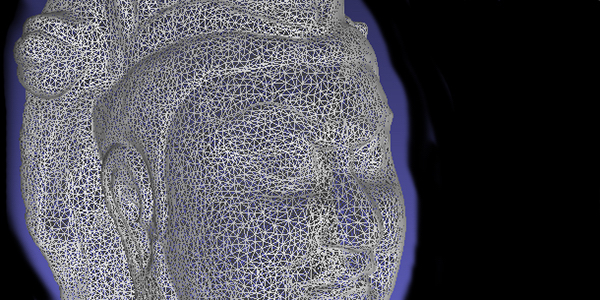

The Buddhist cave temples of Tianlongshan (Heavenly Dragon Mountain) are located in the mountains thirty-six kilometers southwest of Taiyuan city in the central part of Shanxi province. They exist today in a damaged state with so many of the sculptures now missing, that visitors to the caves cannot imagine how they looked in the past. Many of the sculptures from the caves are now in museums around the world. However, though the sculptures may be preserved and displayed, visitors to museums cannot understand them in their original historical, spatial, and religious contexts. For these reasons the Center for the Art of East Asia in the Department of Art History at the University of Chicago initiated the Tianlongshan Caves Project in 2013 to pursue research and digital imaging of the caves and their sculptures. The Project seeks to record and archive the sculptures and to compile data that can identify the fragments and their places of origin. In carrying this out, the Project aims to foster better understanding of the sculptural art, the history, and the meaning of the Tianlongshan Caves through creation of this website and through an exhibition of the results of the Project based on digital information.

A Brief History of the Caves

Known formerly as Bingzhou, this area of Shanxi province had a historical city known as Jinyang since the Eastern Zhou period (8th-4th centuries BCE). In the sixth century CE when the cave construction began at Tianlongshan, Jinyang was the secondary capital and military powerbase of the Eastern Wei (534-550) and Northern Qi (550-577) dynasties. It continued to be strategically important for control of north China and warding off northern incursions into China through the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618--907) periods. Cave construction began at Tianlongshan during the sixth century in the Eastern Wei and Northern Qi dynasties. With the defeat of the Northern Qi by Northern Zhou, Buddhism was suppressed but revived with the establishment of the Sui and continued to flourish in the Tang, when most of the caves were created.

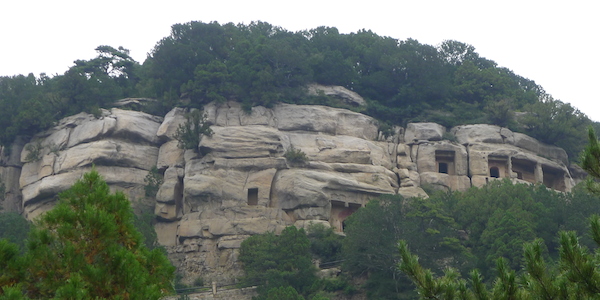

The mountains west of Jinyang were places of retreat and meditation for Buddhists and Daoists. Buddhists established numerous monasteries, some of which were associated with cave shrines and colossal stone images. Tianlongshan is the largest cave site in scale and number of caves in this region. There are twenty-five caves at the site, the most important ones numbered from 1 to 21. The caves extend for about 500 meters across two sections of a south-facing cliff, Caves 1-8 in the east sector and Caves 9-21 in the west sector. The west sector is located above the Tianlong Monastery, also known as Shengshou si (Monastery of Noble Longevity), which is recorded to have been established in the Northern Qi period. The caves were cut into the south facing side of two adjoining sandstone cliffs, mostly from the sixth through eighth centuries.

There is little recorded history or written evidence for dating the caves. Though people who sponsored cave-making frequently carved dedicatory inscriptions in stone, very few are preserved at Tianlongshan. Among those still in existence is the stele in front of Cave 8 recording its creation in the Sui dynasty and dated 584. A second stele that stands at the entrance to Cave 16 is probably from the Northern Qi period, but its inscription is mostly lost. Another inscription on a free-standing stele preserved at Tianlongshan is dated 975 in the Northern Han dynasty, one of the Ten Kingdoms established in the north after the fall of the Tang dynasty. It records the repairs and refurbishing of the large wooden structure that housed a Maitreya Buddha and other stone images, in what is now known as Cave 9. It also records construction of a Hall at the Tianlong Monastery and the casting of a thousand Buddha images in iron. According to a Ming dynasty record of the rebuilding of the monastery, caves were made at the site as late as the sixteenth century.

The sculptures of Tianlongshan are among the finest in Chinese history, particularly those of the Tang dynasty. In the 1920s, the caves received international attention when they were first published with photographs showing their fine sculptural groups. Scholars, collectors, art dealers, and museum curators recognized their value as works of art, and soon the sculpted images cut from the walls of the caves made their way into the international art market--at first the heads, then figures of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, hands, and relief carvings in a second wave of destruction. Some of the figures that were missing their heads were fitted with newly made heads before being sold. The Tianlongshan Caves Project has confirmed the location of over a hundred figures and sculptural fragments from the caves, now located in museums and private collections around the world.

Selected Bibliography

Li Yuqun and Li Gang. Tianlongshan shiku [The Tianlongshan Caves]. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe, 2003.

Matsubara Saburō. Chūgoku bukkyō chōkoku shi kenkyu [Research in the history of Chinese Buddhist sculpture]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1966.

Mizuno Seiichi. Chūgoku no chōkoku [Chinese sculpture]. Tokyo: Nihon keizai shimbunsha, 1960.

Siren, Osvald. Chinese Sculpture from the Fifth to the Fourteenth Century, 4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925.

Sun Di, ed., Tianlongshan Shiku (Tianlongshan Grottoes), Beijing, 2004.

Tomura Tajiro. Tenryūzan Sekkutsu [Tianlongshan Caves].Tokyo 1922.

Tsiang, Katherine Renhe 蒋人和. “Worldly Buddhist Icons: The Global Distribution of Sculptures from Tianlongshan,” in Wu Hung and Guo Weiqi, ed. Shijie 3 Zhongguo yishu shi yanjiu [World 3: Research on Chinese Art History A Western Perspective] (Shanghai renmin chuban she, 2020), 94-111.

Tokiwa Daijo and Sekino Tadashi. Shina Bukkyo Shiseki (Buddhist Monuments in China). Tokyo: Hōzōkan, 1939-41.

Vanderstappen, Harrie and Marylin Rhie. "The Sculpture of T'ien Lung Shan: Reconstruction and Dating," Artibus Asiae, 27 (1964-65): 189-220.